- Home

- Rosemary Manning

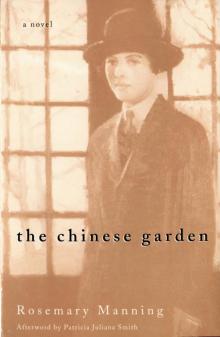

The Chinese Garden Page 4

The Chinese Garden Read online

Page 4

For what world was I searching on these occasions, when the urge came upon me to hide even from my closest friends? I did not know. I was aware only of a private delight in and need for the secret places, a delight which was different from the child’s pleasure in secrets, and a need greater than the mere desire to escape from school. Bampfield so satisfied a part of my personality that I had no desire to escape from it. But there resided within me, the schoolgirl Rachel Curgenven, another self, a restless, hungry, immaculate being, bent on piercing through the outward semblances of things to seek out another intuitively-known reality, a reality beyond the world as I saw it. Without being aware of it at the time, I brought back, perhaps, no more than the word ‘fire’ or the word ‘rose’. But these images flowered for me in the deserted gardens of Bampfield, and they never withered.

Poetry was the bridge over which I walked to this world which, at sixteen, I was already in danger of losing sight of.

Names, deeds, grey legends, dire events, rebellions,

Majesties, sovran cities, agonies,

Creations and destroyings.

I became intoxicated with the power of poetry to transport me into this other world and resentful of sharing the peaceful places. Only when I was alone could I experience the ‘shades and silences and the voices of inanimate things’. They acquired for me a quality of near-perfection, owing to their withdrawn, uncontaminated peace. The lines of their formal beauty remained, the paths could be traced, the urn still stood on its crumbling base, the dry fountain could be seen above the rushes. The image in the eye of whoever had created it still lay behind its dereliction, could be recaptured by my own imagination. It was at the time of my sixteenth birthday that I first became conscious of the power of such images over my being. The sunrise on the November morning remained more vividly in my own mind than in the words in which I had tried to re-create it and share it with others. When I thought of Margaret’s still untold secret, I realized that she might have regretted the impulse that made her begin to tell us of it, and I recognized that she had the right to keep it to herself, to preserve it inviolate. Some bond of sympathy between myself and Margaret reduced my curiosity to manageable proportions.

Lying in bed, the morning after the storm, watching the rain, I was almost glad that it would probably be impossible for her to reveal the secret today.

CHAPTER SEVEN

This was my shaping season.

HENRY VAUGHAN

DAY after day it rained with West Country persistence. Rachel threw herself resolutely into her Virgil translation, finished it at last and gave it to Miss Burnett. Bampfield was sodden and inert. Chief had not appeared for days. It was given out that she was ill, and the withdrawal of her presence took the salt out of the regime. At last, the rain cleared and a faint watery sun hung luminous in the sky, giving little warmth but cheering to the eye. Tempers grew easier. No longer confined to form-rooms, the girls ran about the muddy park; windows were opened, and the building began to breathe freely again. Chief recovered. Rachel saw her coming slowly down the front staircase one morning and at once went to her assistance. It was the recognized thing that you offered Chief your shoulder to lean on, coming down stairs. At the bottom, Chief did not relinquish her hold.

‘What are you supposed to be doing, Curgenven?’ she asked.

We were almost invariably called by our surnames at Bampfield.

‘Drill, Chief, I was just going down to change my shoes.’

‘Ah, yes, drill,’ said Chief, as though hearing of the subject for the first time. ‘Never mind, I want to talk to you. Come out into the sun.’

The two walked slowly out, and across the front sweep on to the sodden grass.

‘Isn’t it awfully wet for you?’ asked Rachel protectively.

The habit of protection was well developed in the older girls.

Chief ignored her remark, and leaning heavily on her shoulder gazed at the distant hills.

‘That’s a very good piece of work you’ve done for Miss Burnett,’ she said slowly. ‘Very good indeed.’

For a moment Rachel did not understand her. ‘My … my last prose, do you mean, Chief?’

Chief shook her shoulder playfully. ‘No, no,’ she said. ‘Your translation.’

‘Good lord, has Miss Burnett shown it to you?’

‘Certainly. I read it through last night. I couldn’t put it down until I’d finished it. I’m very glad you did it. It is things like that that make teaching worth while.’

Behind them on the cruel flints, the rest of Rachel’s form was having drill, making teaching worth while for Miss Christian Lucas. Chief and Rachel walked slowly up and down the hockey pitch, Rachel silent, Chief meditative, speaking from time to time at random, about Virgil, about the pitch, about the prospect of the park.

On this damp November morning, the voice of Miss Christian Lucas, absorbed by the spongy atmosphere, receded as Chief and Rachel went further down the pitch. Half-hypnotized, Rachel suspended both her hatred of Miss Lucas and her morbid passion for the drill itself, and allowed herself to be wholly subject to Chief’s personality. She had suddenly started a new subject.

‘You will have to be a prefect soon. How do you feel about it?’

No false modesty was expected. Chief uttered the words as a challenge. True to her Bampfield training, Rachel replied, ‘I’m ready when you choose to make me one, Chief.’

‘Really? Are you ready?’ Chief looked at her shrewdly. ‘You have still some way to go, I think, but it is something that you feel yourself ready, for that means that you are prepared to train yourself further. Is that so?’

‘What do you want me to do, Chief?’

‘You must regard yourself as a squire, training to be a knight. The positive qualities I think you possess – a sense of leadership, an air of authority. But there are things you will have to do without. You must remember how an acolyte, before taking his vows, fasted. You will have to learn to fast. Must I tell you what you will have to do without?’

No, it was not necessary. Rachel felt she already knew. Her friendship with Bisto, possibly. Her friendship with Margaret, certainly. A prefect was understood to embrace a vow of non-friendship, much as a knight espoused lady chastity. It was a Bampfield rule.

The two turned and walked back in silence. The voice of Miss Lucas became more insistent.

‘Knees outward…bend!’

The flints grated beneath twenty pairs of ravined plimsolls. Chief paused. The girls were now running, marching and counter-marching, their breaths coming in uneasy gasps.

‘She trains their bodies,’ said Chief with admiration, watching the precision of the ranks. ‘Only you can train your mind, your own personality. With of course, the help of Gud. It is a matter of the will. Train your will first, Curgenven, and all else shall be added unto you.’ She leaned a little more heavily on Rachel’s shoulder. ‘Next year I shall make you a prefect.’

Chief released her, and walked back into the house alone, leaving Rachel standing on the empty hockey pitch, moved and appalled, like a neophyte who has attended some fascinating but revolting rite.

In the park among the decaying branches and ashen trunks of the dead sycamores and elms stood a few young trees, planted before the school took over the estate, and left uncared-for ever since. Each had been given protection from the deer and the rabbits by a circlet of iron paling, to which netting was fastened. The netting had long since rusted into shreds, but the palings remained, close now to the bark they had once protected, and doomed, as the trunks swelled, to throttle the trees more and more tightly, till, like the iron bands of a medieval engine of torture, they cut into the living bark. I see now a symbolism in the deeply scarred trunks. All the ambivalence of my attitude to Bampfield is summed up in that short conversation with Chief as we strolled the playing fields. I despised the regime, laughed at it, rebelled against it, yet I was subject to its fascination. I could not detach myself from it and readily rendered up my personality

to its peculiar power. It could not restrain my growth, but, like the iron bands encircling the trees, it could and did mark me.

CHAPTER EIGHT

To submit myself to all my governors, teachers,

spiritual pastors and masters …

THE CATECHISM

THE school which framed our youth was founded in about 1919 by a group of friends who had met and worked together in V.A.D. hospitals during the Great War. The Caesar of this triumvirate was Delia Faulkner. The Lepidus, who provided the money for the venture, was a Mrs Watson, a widow with a small girl. The Pompey – though here the comparison is less apt – was Miss Gerrard, a brilliant organizer and campaigner in the field of education. Later, a fourth and much younger woman, Miss Murrill, had been added to the group.

Miss Faulkner was always called Chief. Not the Chief, but simply Chief.… ‘Yes, Chief, no, Chief.’

The school was an amalgam of Sparta, Rugby and Cheltenham Ladies’ College. The first dictated the details of our physical life, the drilling in wind and rain, the cold washing water, the bad food, the inadequate heating and bedding, the hateful runs before breakfast. The third, Cheltenham, contributed the moral tone of the school, but the second influence, that of a boys’ public school, was in some respects the most far-reaching, for it governed our social relations with each other and with the staff.

This Bampfield ideal was designed to turn us into English gentlemen, sans peur et sans reproche. In justice to boys’ schools, it must be confessed that the discipline savoured more often of a prison camp than of Eton or Rugby. We marched everywhere in line and in step – to meals, to prayers, to bed. Silence must be observed in every passage, and during part of every meal. No personal possessions were allowed except clothes and similar necessaries. A photograph or a trinket was confiscated at once, if found. We wore a severe uniform which never varied, winter and summer, and which, without being actually masculine in style, succeeded in reducing our femininity to unnoticeable proportions.

Though Chief could not alter the physical appearance of the children completely, she did alter her own. She wore her hair severely cropped like a man’s. Her face was of a masculine cast, the nose slightly aquiline, the forehead smooth and high, the chin firm and finely moulded – a remarkable face. Summer and winter, she invariably wore a silk shirt, with detachable soft collar, and a silk tie, under suits which were made for her, of good grey suiting, and cut in as masculine a style as they could be without the actual substitution of trousers for a skirt. When she went out, she wore a green pork-pie hat, and a heavy camel’s-hair coat, which I believe was actually bought in a men’s shop.

She was not tall, and inclined a little to fat when I knew her, but she was very finely made. Her bones were small and delicate. Her hands, in particular, were of great beauty and she used them expressively. Her mouth could express an extraordinary sweetness, but it was marred by her teeth, which were brown and irregular. Her eyes were a light colour, a kind of greyish hazel. In the old photograph I have of her, and often as I remember her in real life, they had an infinitely sad and haunted look. The spark of her will usually flashed from them, and so dominant and piercing were they that they almost hypnotized one. But in repose, and under the revealing eye of the camera, the scared, unhappy woman that existed in that elegant, tailored dummy, stood out as clearly as ancient earthworks under the turf are revealed by an aerial photograph. A world of mystery lay behind those extraordinary eyes. I used to long to know more about her, but I never discovered very much. According to her own account, she came of an old East Anglian family: she had gone on the stage; she had left it for reasons of health; she was an M.A. of Leeds University (this I never, even at school, believed. I was persuaded that she had selected this university as her Alma Mater partly for its remoteness and partly for the beautiful colour of its Master of Arts hood – a rich blue – which she always wore on Sundays); she had been a V.A.D., and the Matron of a war hospital; and after the war she came to Bampfield to educate girls in accordance with her peculiar principles, certainly no typical schoolmarm, but no normal woman either.

Seated behind her desk, the cropped head above the dark, well-cut suit, the immaculate collar and tie with its unostentatious pin, she gave one the impression of ineluctable masculinity. Parents seemed to find this unexceptionable, and accepted with equanimity the statement that their daughters were to be brought up as public school boys. I can only regard this as a twentieth century refinement of the primitive habit of exposing girl children to perish in earthenware jars.

Chief suffered from what is vaguely termed a weak heart. In 1918, doctors had told her that she was unlikely to live longer than a year. She was then in her early or mid-thirties. She lived, in fact, to be over sixty. And so extraordinarily potent was the spell that she cast over all who knew her, that when I heard of her death, even though I had not seen her for years, and had come to understand Bampfield for what it was, it moved me profoundly, and for days I could think of little else. It was then that there came into my mind an occasion – rather dim to me – which I had not recalled in all the years since I left the school. It hangs now ineffaceably upon the walls of my mind like one of those Netherlandish pictures of the seventeenth century in which a little scene – a figure poring over a manuscript, or a shepherd looking down at the Child in the manger – glows out from a small patch of light amid a surrounding expanse of black canvas. So I see Chief lying on a couch one winter’s night, and the couch was not in her study, but up on the wide first-floor gallery. We were coming up the staircase which divided and ascended to either end of the gallery. The hall lights were out and the corridor itself in darkness. Only the little group round the couch was clearly illuminated. And Chief was dying, it was whispered. One by one we came up to the couch and in hushed tones said good-night to her. We had been told that it was her wish to lie there and see us as we went to bed, to hear our voices bidding her good-night for the last time. She herself did not speak. She recovered, and the incident was never referred to again.

She willed herself to live. The will for her was the most important attribute of human nature. Her creed was not so much ‘Nothing is impossible to him who believes’, as ‘Nothing is impossible to him who uses his will-power.’ Having proved to herself the undeniable advantages of willing herself alive, she was eager to pass on these benefits to others. Self-control was the watchword of Bampfield, and I am inclined to think there was a fundamental confusion in Chief’s mind between the active principle, the will, and the passive virtue of silent endurance. She herself undoubtedly possessed exceptional power of will which enabled her to endure pain and sudden helplessness without complaint, and also perform, and even more often force others, against all odds and opposition, to carry out work she wanted done. I admired her then and I admire her now for that immense, indomitable will-power which kept not merely material difficulties and physical weakness at arm’s length, but compelled even Death himself to wait outside the door till she was ready for him. But for children there were no such high stakes. Death and worldly disaster were remote from us, and provided no noble exercise for our powers, which in any case would hardly have been equal to a combat with such majestic antagonists. No, it was our task to strengthen and train our wills in the limited field of school reverses and discomforts, that we might face and overcome the struggles of adult life, the world, the flesh and the devil. To this end generous opportunities for self-denial and endurance were provided at Bampfield.

None of us ever complained. Indeed, why should we? We were told by Chief over and over again that it was ‘our’ school, and we really believed it. The discomforts seemed perfectly legitimate, like bunkers on a golf course. At any rate, I know I came to regard them in very much that light, as a test of skill and endurance. I learned to accommodate my person to the lumps in the flock mattress and my stomach to the bread and margarine which was our staple diet, while my spirit was fortified by the noble words of Galsworthy which I heard at least a dozen times every te

rm, for it was one of Chief’s favourite poems (I hope I remember it correctly):

If on a Spring night I went by

And God was standing there,

What is the prayer that I would cry

To Him? This is the prayer:

O God of Courage grave,

O Master of this night of Spring!

Make firm in me a heart too brave

To ask Thee anything.

We must have felt that not only God, but Chief, was standing there, and a very palpable presence at that. Whatever secret petitions we might in our inner weakness have directed heavenwards, we certainly would have been ashamed to proclaim our cowardice by asking Chief for any remission of our hardships.

Dictator though Chief was, the other two members of the triumvirate which fenced us from the world were more than mere lackeys. Each of them possessed a character of iron, which, joined by the rigid band of a common and apparently uncriticized ideal, dictated the shape of our youth.

The School was called Bampfield Girls’ College. I think Miss Faulkner would have liked to call it Bampfield Ladies’ College, since Cheltenham was one of her working models, but she hesitated at the plagiarism, and later even the ‘Girls’ was dropped. The reason for this was, I believe, that she had come by this time to regard us all as boys and did not wish to be reminded of the biological facts.

The Chinese Garden

The Chinese Garden